Cake in Taiwan

It's the 1990s, and I'm in elementary school. Every year during spring break, my family caravans with Taiwanese friends from Cleveland to Toronto, where we can find handmade tofu, gigantic dim sum halls, and mangoes. While my friends share a bag of marinated chicken hearts, I press onward to the Chinese bakery. Inside, sugar and flour mingle in the air, their scents fortifying me as I scan the rows of cakes. Beside me, my brother picks out something custard-filled and my dad chooses a pastry with taro. My mom picks up their selections with the tongs, leaving room on the tray for my favorite.

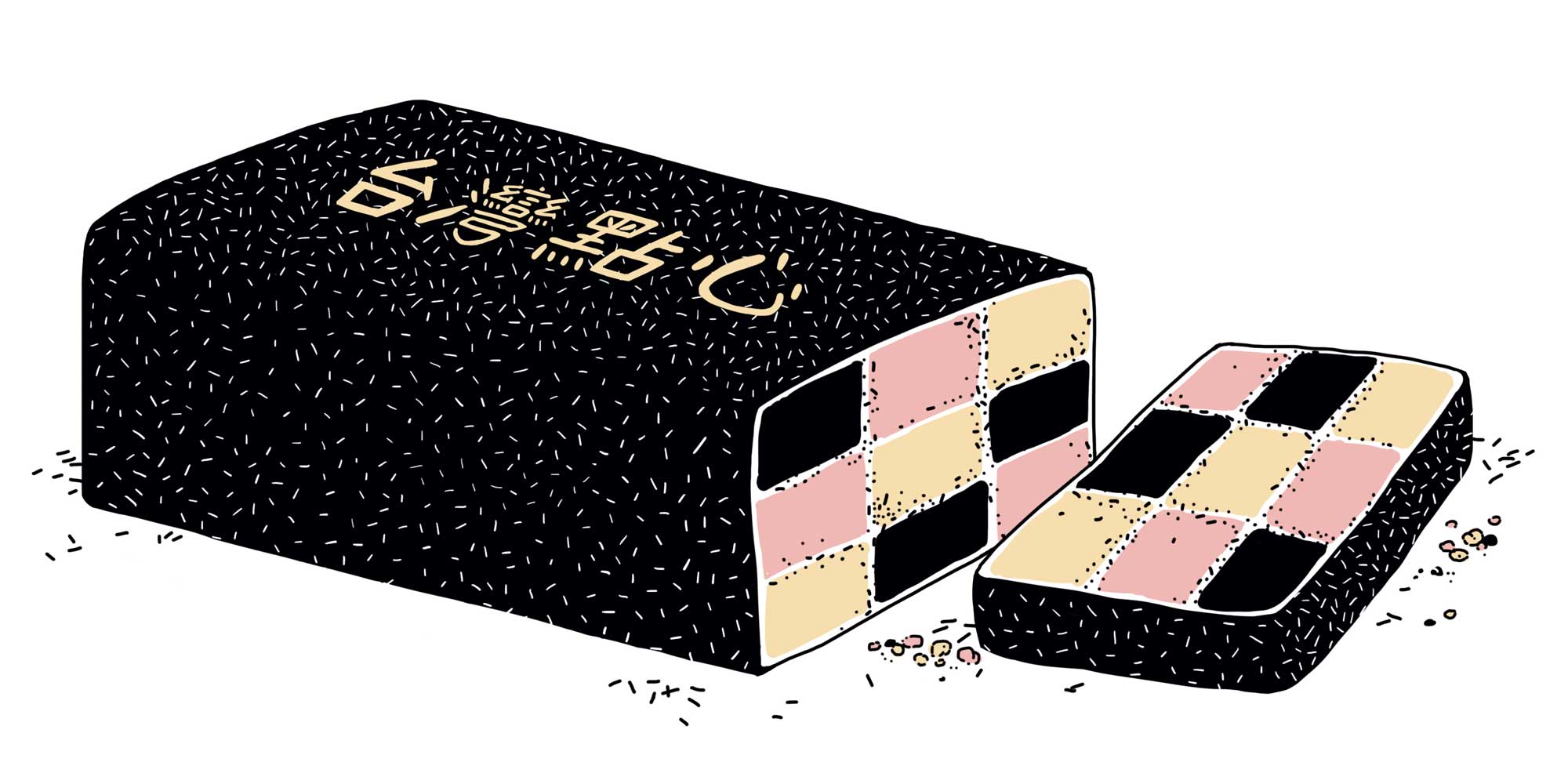

The tricolor cake (三色蛋糕 sanse dangao) is sliced to show blocks of chocolate, vanilla, and pink cake stacked in a beautiful checkerboard and wrapped in a fine coat of chocolate sprinkles. The next morning, when I have a slice of the tricolor cake for breakfast, I am careful to eat the colors in order: a vanilla block, a chocolate block, then a pink block (the most exciting!) before returning to vanilla. Naturally, I save the pink corner block – with its extra chocolate sprinkles – for my last bite. It was a breakfast worth the six-hour drive.

Now that I live in Taipei, I’m only two blocks away from my favorite Taiwanese pastries and snacks, and I take every opportunity to conduct firsthand research at bakeries. Beyond these taste tests, I consult various secondhand sources, too – my relatives and coworkers, who can be quite vocal in their preferences and descriptions of Taiwanese cakes. I’ve come to discover that many of the foods known in English as “cakes” are actually a diverse range of Taiwanese snacks. For example, my beloved tricolor breakfast slice belongs to the dangao 蛋糕 (“egg cake") category; with its soft, spongy crumb, it looks and tastes like a Western egg-butter-sugar-flour cake. Likewise, though the Black Forest dangao eaten in Taiwan is lighter than the American (or German) version, the resemblance is clear: layers of chocolate cake, whipped cream, and cherries.

However, the other “cakes” on Taiwanese bakery shelves are likely to be savory, flaky, chewy, sticky, or crumbly. They may contain radish, red bean, mung bean, sesame, salted egg yolks, ground peanuts or wintermelon. If these don’t sound like cake ingredients, just remember that these foods are united by an accident of translation. Cake is just their English name. In Taiwan, they actually belong to different texture tribes: gao 糕, bing 餅, and su 酥.

糕 gao

Gao starts with a batter and ends with steaming or baking, so the finished product ends up having a fairly homogenous consistency from top to bottom, whether it is a wheat flour crumb or sticky rice flour pudding.

蘿蔔糕 luobo gao, aka "radish cake"

Savory radish cake is delicious – soft slabs pan-fried to a golden brown and dipped in garlicky soy sauce. To prepare it, white radish is grated and sautéed, then mixed with rice flour, radish juice, and water, and finally steamed until it forms a solid pudding that cools into a dense, chalky brick. It will keep in the fridge for a week, so my mom gave me a brick of this gao to slice and pan-fry in my college apartment. Excited to share this snack with my roommate, I told her that the radish cake was in the fridge if she wanted to try it before I got home from class.

To the uninitiated, the words “radish cake” may sound like a Taiwanese variant on carrot cake, the classic American dessert.

Later that evening, my roommate told me she’d sampled my mom’s radish cake – and frankly, found it disappointing. “I know you like it a lot, but the piece I took from the fridge was a little bland. I even drizzled honey over it!”

年糕 niangao, aka “New Year’s cake”

My roommate might have had better luck with Taiwanese niangao, which is a sweet, punny New Year’s cake made from sticky rice flour. Nian (“sticky”) is a homophone for “year.” Gao sounds like the word for “high” – you eat this sticky cake because you have high hopes for the new year! Even niangao isn’t at its best straight out of the fridge, though. My mom slices niangao, batters them in a cornstarch slurry, and shallow-fries them into a sticky, stretchy treat for good luck in the new year.

餅 bing

Bing can be either sweet or savory, but this type of cake is known for its crust. Fillings like red bean paste or black pepper and ground pork are wrapped in laminated dough. As you bite into the pastry, the buttery (or traditional lard) crust flakes off to reveal the juicy meat or sweet filling inside.

月餅 yuebing, aka “mooncake”

The mooncakes sold in Chinese supermarkets and bakeries in North America are the Chinese style, shaped in molds engraved with the names of the fillings, so you know what you’ll taste when you bite into the cake. Taiwanese-style mooncakes are smooth and spherical. Each ball of filling is encased in laminated dough; when the mooncake comes out of the oven, the layers of fat have transformed it into a flaky crust. The baker inks the finished mooncake with red food coloring to indicate the filling. Pale mung bean paste, li bai 李白, is named after the famous Tang dynasty poet, whereas su dongpo 蘇東坡 mooncakes have an unctuous pork filling named for the Song dynasty poet.

Mid-Autumn Festival falls on the biggest full moon of the year, and it also happens to be my lunar birthday. Every year, I celebrate twice: butter/oil cake for my Gregorian birthday, and mooncakes filled with red bean paste or pineapple for my lunar birthday. With the vast selection of mooncakes in the days leading up to Mid-Autumn Festival, I could choose a "Taiwanese birthday cake” as big as 4 inches in diameter, but I prefer the smaller mooncakes (ice-cream scoop-sized) for the perfect filling-to-flaky-crust ratio.

太陽餅 taiyang bing, aka “sun cake”

Sun cakes might just be my favorite Taiwanese snack, and they aren't tied to my birthday or a national holiday, so it's easy to find them every day of the year! People debate whether the crust is flakier with pork fat or butter, but I care more about the sugar inside. Although you'll find brown sugar or honey versions these days, the best version is the traditional maltose flavor. This kind of sugar is “wetter” than sucrose, so it’s a bit gooey and chewy inside the sun cake. If you leave a sun cake for too long, the maltose inside does eventually harden, but I usually finish my sun cakes long before that point.

My preference for maltose might be genetically imprinted. My mom tells stories from her childhood about how exciting it was whenever the sugar-blowing artist came to her neighborhood. Children would rush outside to watch him create fantastic maltose sculptures, building sugar animals on the ends of chopsticks. They also made sure to bring their own spoons to scoop up the molten syrup, letting it harden into lollipops to savor.

囍餅 shi bing, aka “wedding cake”

Cast aside your notions of frosted tiers. These 8-inch discs – with flaky crusts enclosing red bean paste, peanut powder, sesame, walnut, or other sweet fillings – are delivered along with wedding invitations to guests on the bride's side. The most traditional shi bing add some savory to the sweet, layering pork crumbles inside.

Because she moved to the US 30 years ago, my mom has missed out on most of her relatives’ weddings – and all the accompanying cakes. Knowing how much she loves shi bing, her own mother prepares for visits by ordering a stack to lug to the States. Seeing the order for 20 cakes, the baker always asks my grandmother, "Oh, is your daughter getting married?"

酥 su

Su pastry is made with shortening. My coworkers offered so many different examples from all around Taiwan that it was difficult to generalize the appearance of su, but one summed it up by saying, “It’s messy to bite into. Crumbs fly everywhere!” In contrast to the flakiness of bing, su tends to crumble.

鳳梨酥 fengli su, aka “pineapple cake”

In the 1990s, the pineapple cakes found in Asian grocery stores were Fig Newton-like snacks just bigger than a mahjongg tile. The filling mixed pineapple with wintermelon, and they were sold in plastic trays like any other soft cookie. In the past decade, however, a single pineapple cake maker, SunnyHills, revolutionized the industry when they began producing pineapple cakes that were 1 x 1 x 3-inch bars filled with unadulterated fruit. The founder’s family estate in Taiwan’s Nantou County now fills every weekend with visitors eager to try pineapple cakes that derive their tartness from local pineapples (土鳳梨 tu fengli). SunnyHills has an agreement to rotate among the neighboring farmers so that their fields have time to recover after each harvest. Competitors took note of their success; nowadays, most Taiwanese bakeries sell bar-shaped pineapple cakes as a premium product.

花生酥 huasheng su, aka “peanut cake”

This last snack may seem the least cake-like, even if it shares the su nomenclature with other snacks. My mom's hometown in Changhua County is known for producing a peanut su that swirls fragrantly toasted peanut halves into nuggets of brittle. When you bite into one, there is a satisfying crunch as the crumbs fly. In other parts of Taiwan, peanut su connotes sheets of peanut floss that are rolled and cut into squares. The airy confection tastes like spun sugar, but it’s more powdery than its appearance would suggest.

As you can see, some of these “cakes” are more like hand pies or puddings, and still others have no easy Western analogy because they are so steeped in Taiwanese ingredients and traditions. That’s not to say that Taiwanese cakes are unchanging. Thanks to local innovation, shiny new bakeries are constantly popping up amidst a landscape of traditional ateliers. Last Mid-Autumn Festival, my uncle gave me a box of cranberry-and-cheese mooncakes; meanwhile, my coworker opted to celebrate her wedding with tins of French sable cookies instead of the shi bing my mom remembers from her youth.

The diversity even shows up in the nomenclature. While the transliterations I’ve used are the Mandarin words, there are further variations in Taiwanese (a dialect of Hokkien). For example, the gao 糕 of “egg cake” is pronounced guh in Taiwanese, but the gao 糕 of “radish cake” is pronounced guei. Some of these snacks have separate Mandarin and Taiwanese names, the blend of food and language reflecting migration between China and Taiwan. Baked into all of these words is the history of the foods, colonization, diplomacy and the people who eat them.

When these pastries and snacks were brought to America, they – like many immigrants – experienced a fateful moment the first time somebody asked their name. An easy-to-remember English name was chosen for them that overwrote their complex history. Sweet and savory, flaky and gooey – all were consolidated under “cake.”

Immigration necessitates assimilation, but as long as Taiwanese immigrants crave pastries that taste like their childhood, the recipes for these gao 糕, bing 餅, and su 酥 will continue to cross borders – bringing comfort even as bakers add novel ingredients and fresh customs.

text by Cindy Lee, illustrations by Julia Kuo

Cindy Lee would have finished school much sooner if she had majored in cake. Now, she sciences in Celsius and bakes in Fahrenheit, so you can discuss relevant findings with her on Twitter @geneandtonic or at genesandtonic.wordpress.com

Julia Kuo is a Taiwanese-American illustrator working out of Chicago for most of the year and Taiwan in the winter. She has been an artist-in-residence at the Banff Centre, illustrated several books, and worked with clients such as the New York Times, Fendi, and Simon & Schuster. Her favorite pastimes are climbing, hiking, and dreaming about summiting faraway mountains.