Shuffle Master Of The Universe

“Ready?” my father asks, his voice booming, cutting through the din of the hospital room. He bends toward my grandfather, Ye Ye, who is sitting on the edge of the bed, and grabs him by the armpits. I touch Ye Ye on the shoulder, and even though I can feel all the way to the bone, I get the sensation of dredging through mud with a wet paper towel. His skin stretches and responds, but not his body.

“Okay. Up we go! Stand up!”

Ye Ye groans as he is pulled off the bed. He looks down and giggles as if we’re playing a game where he’s supposed to move around the room without touching the floor and he’s clearly winning. “Hee hee!”

The male nurse says to me, “I’ll take the other side. His legs are buckling again. Here, set him down.”

My father and I lower my grandfather on the bed. His white hair floats up, then down as he makes contact with the mattress.

“Can you move that thing closer?” the nurse asks, kicking out a foot to hook one of the wheels of the portable toilet.

I let go of my grandfather’s arm to reposition the toilet. Viewed from the back, the toilet and my grandfather, who once stood almost six feet tall, look similar in size and posture.

The nurse says, “On the count of three.”

“One.”

I brace the back wheel of the toilet with my foot.

“Two,” my father and the nurse each take a lunchmeat-colored forearm.

“Three!” My father and the nurse hoist Ye Ye into the air. He’s so light they overshoot the seat by about two feet. Ye Ye is giggling again as he levitates. Before they land him the nurse adjusts his gown so that the fabric is respectfully piled up on his lap.

“There you are,” the nurse says.

“Okay,” my father commands. “Now poop.”

It comes. Like a rainy night in Georgia, a torrent long and wide hits the hard bucket. The plastic is tough and opaque but there’s enough force in the dark matter to cast shadows of craggy trees and eerie horsemen against its white walls. The odor comes next, cutting into the smiles of relief on everyone’s faces.

“It’s the medication,” my father tries to explain to my grandfather, who is madly sniffing in search of “who dealt it.” Except for his yellow toenails, he looks like a child, swinging his feet and whizzing his head back and forth. Suddenly he spots the nurse and greets him with a lift of his hand. Ye Ye bows his head and smiles politely, signaling that he was finished and the gentleman’s turn was next.

The nurse, toilet paper at the ready, cannot help smiling.

“Tomorrow,” my grandfather says, sitting back with a bemused look on his face, “tomorrow I’m going to buy this place a door.”

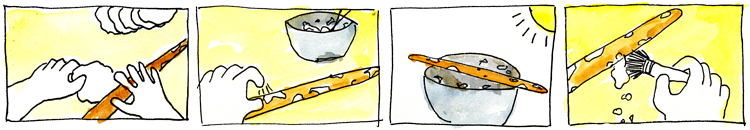

Do not be tempted to wash the wet and sticky dough from your dowel after rolling out dumpling skins. Leave it untouched until the dough dries to a crust and easily brushes away.

In 1999 at the age of 85, my grandfather complained of a headache, took two Tylenols, lost his mind and never got it back. He was living with my father in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where my grandparents had moved to in 1985, after 70-plus years living in China and Taiwan. Since it wasn’t Alzheimer’s technically, just good old regular dementia, after several weeks in the hospital my father felt he would be more comfortable – for a number of cultural and linguistic reasons – if he returned to live at home.

My father was working as a physicist for the Los Alamos National Laboratory and couldn’t be home during the day to be with my grandfather. Luckily, Los Alamos is home to an eclectic community of scientists, and my father was soon introduced to an out-of-work Chinese mathematician. The mathematician offered to take care of my grandfather during working hours – not because he needed the money but because he felt it was his fate to do so. He told my father that he had not been allowed to go back to China to care for his parents before they died, and looking after my grandfather would restore the imbalance in his mind.

Besides, my demented grandfather, who had always been so cold and laconic, had suddenly become “fun.” He was chatty. He giggled. He returned to a time where his memory was still vivid, where he enjoyed imaginary cigarettes with co-workers and worried about where to get lunch.

“You are allowed to make dumplings in your underwear, as long as the dumplings are good”

Every few months, I flew out from Los Angeles to take care of him, and watched his sanity flow in and out. He had regained some of his physical strength but often had no idea who I was. If I called out “Ye Ye,” he’d respond with a jerk of the head that was almost Pavlovian, and if I told him I was the daughter of his only son, he’d often laugh and say he didn’t have a son. If I asked him if he could tell me what my name was, he’d laugh even harder and say, “Such an easy question. As if I didn’t know!”

He’d tell me about people I have never heard of, old pals, and then he’d say, “Call a taxi! Let’s get out of here and get noodles on such-and-such street,” referring to his old neighborhood in Taiwan. When I asked if he was going to get the beef or the lamb, he’d look at me suspiciously as if I were about to steal his lunch money. Other times, he was profoundly lucid, calling my father by his childhood nickname and reading newspaper headlines out loud in English, a language he had studied long ago but never actually spoken. The doctors said his reading comprehension was probably part of his long-term memory, the part of the brain the dementia didn’t zap.

On one of my visits, I asked Ye Ye, “What do you think about making dumplings today?” My grandfather had never been a talker, so one way of testing the waters of his sanity was to see his response to things he used to love to do. Today he paused, almost saddened by the thought. After a few seconds his face lit up, having just scanned the refrigerator of his mind. “Yes! We have those Chinese chive buds!” It was true, though how he knew that was beyond me.

“Okay!” I started to get excited. “What do we do?”

“Oh, we have plenty of time.”

“What time do you think it is?” I asked cautiously.

“Ha ha ha,” he replied.

“Shouldn’t I start the dough?”

“Oh,” he said, rubbing his chin. “It might be too far to walk.”

“I can drive,” I said, hoping to steer the conversation back.

He waved me off and went to lie down on the couch.

Nuke a frozen zongzi, and it will come out with hardened bits of sticky rice that break your teeth. To quickly and safely thaw a frozen zongzi, shelter it under a large bowl and gently warm it on the defrost setting.

Real Chinese food in America is rare enough but Chinese food in Los Alamos is on par with the yeti. My grandparents had succeeded not only in growing Chinese vegetables that were more accustomed to the humid climate of Taiwan than New Mexico, they mixed their own red bean paste, wrapped their own sticky rice zongzi and brewed their own rice wine. When they moved to the US, they left behind my grandmother’s jewelry but brought with them the wok used for smoking duck and a particular cheesecloth ideal for squeezing soybeans into milk. Apparently, when they were fleeing the Japanese invasion of China, my grandmother wept as she ditched her giant soup pot on the side of the road.

My grandmother had passed away several years before Ye Ye’s illness. Like typical grandparents they had very little of their history written down. The recipes they did have were old and vague, with a lot of missing steps, or there were several versions, paper-clipped together with the most recent iteration on top, seduced onto paper by my father.

For example, the recipe for my grandparents’ Wind Chicken (风鸡 fengji) changed from “2 spoons” salt to “4T” and then “roughly 1½-2T” over a period of five years. The modification reads more like my grandparents trying to appease my father’s nagging about their salt intake rather than any type of real direction.

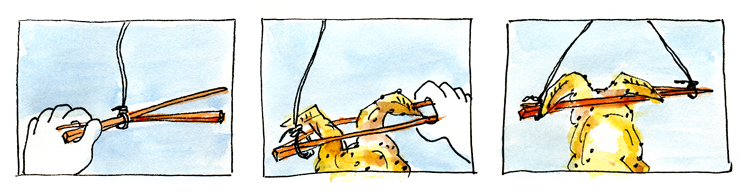

The recipe itself is simple. Take a whole chicken, pat dry, rub it inside and out with some amount of salt and Sichuan peppercorns and hang it up using two chopsticks in an “old home” (老家 laojia) technique for 2-3 days in a “cool and windy yet sunny place” – a place like Taiwan in winter, or a backyard overlooking White Rock Canyon in New Mexico. Let the chicken rest in the fridge for a couple of days. Cut it into large pieces and steam to serve.

"My father once criticized me for painting a portrait of Ye Ye in his slippers."

Neither of my grandparents had been trained as chefs – they were an engineer and nurse-turned-housewife – but cooking to them was all about living in the present. They didn’t bog themselves down with how they did it last time, or how they would do it in the future. They just cared about this piece of meat, this one carrot, this can of broth.

Improvising as they went along, they relied on years of experience and intuition to determine how long to soak or boil things. Sure, they lamented the lack of Yunnan ham or whole black chickens in America, but they were able to adapt on the spot. It’s called the zone – being able to feel one’s way toward a solution rather than think. Thinking leads to overthinking. We’ve all seen it happen. In sports it’s called choking. In restaurants it’s known as overcooked meat. The body has to overtake the mind.

My father, the consummate physicist, has never understood this. He thrives on precision. He makes the same meals the same way every time, since that’s the way he likes it and that’s the way he does it. To his credit, he makes a lot of different dishes, and they all taste good and distinct from each other. But each dish satisfies the rigorous scientific test of repeatability.

A piece of baked tofu is cut in half, then each half is sliced into three slices, and then cut into strips. God forbid you do it any other way. The same is true for watering fruit trees. Turn on the hose so that the stream of water is one half the width of your pinky. Let drip for 45 minutes. The line to fill the water to in the rice cooker is 1/8th inch above a particular ding in the metal pot. To boil eight ounces of water, place the cup in the microwave for exactly one minute and 50 seconds on high. Measurements for slicing vegetables are given in 1/16th-inch increments or in percentages. Both my brother and I are extremely adept at dividing a pie into five equal pieces. Anything that has to do with dough, or variable percentages of ingredients baffles him; those dishes have never made it into his repertoire. Dad’s always been frustrated by the phrase “add as needed.”

Obviously, he’d be ecstatic if the dumpling master found an apprentice.

To hang Wind Chicken laojia-style, assemble two feet of kitchen twine and a pair of bamboo chopsticks. Point the chopsticks in opposite directions and lash them together at one end. Sandwich the chicken between the chopsticks as close as possible to the base of the wings. Using the other end of the twine, bind the other side, tightening both knots to secure the chicken.

After Ye Ye’s nap I heard a toilet flush near his bedroom. When he emerged he had a big smile on his face and a long wet stain on his pants. Sometimes his fingers fumbled too long with his zipper. Sometimes he lost his balance in the bathroom and leaned backwards as he peed. In any case, he never heard of a man who peed sitting down, and he definitely refused to wear a diaper.

“Do you know who I am?” I asked.

He smiled.

“Who am I?”

“Ready?” he said with a goofy grin.

I pointed to his crotch. “Let’s change your pants first.”

“Nah,” he said, dismissing me very curtly.

I made a hand motion urging him back to his room.

“We’re making dumplings,” he blurted.

“Pants first?”

“Dumplings.”

“Please?” I said, looking sad.

“Okay,” he said, dropping his pants right there and shuffling to the kitchen in his baby blue boxers.

After finding a clean pair of pants and threading his belt, I joined him at the table, reunited with the yellow Tupperware flour container and the red measuring cup I had known all my life.

“Did you wash your hands?” he asked, elbowing me away from the stainless steel bowl. He clearly didn’t believe me.

“Yeah, yeah.” I handed him clean pants. I don’t know if mise-en-place applies to being dressed appropriately in the kitchen, but I do know there isn’t an equivalent phrase for such nonsense in Chinese. You are allowed to make dumplings in your underwear, as long as the dumplings are good.

“If you washed them, then you washed them.”

What about you, buddy? I smiled and said nothing.

“So what’s the ratio?” I asked, taking the lid off the tub of flour.

He cocked his head to one side. “Three to one.”

“Three what?”

“Three cups water to one cup flour.”

“Really?”

“Maybe it’s four.”

“Are you sure it’s not three cups flour one cup water?”

“No. It’s four.”

“One – two – three.” He poured three cups of flour into the bowl and then sat there, staring at the bowl. Slowly, he added one cup of water. “Four. See?”

Using chopsticks to work the dough in tight little circles, he added a little more flour, a little more water and then a little more flour. He kept mixing until the water and flour came together, leaving the sides of the bowl almost clean. Then he emptied the bowl onto the counter and started to knead.

After several minutes the dough formed a smooth ball. He pinched it several times and nodded. It looked pretty good to him and it looked pretty good to me. He dropped the ball back into its bowl, battled a stubborn piece of plastic wrap and took a seat at the table. As soon as he turned his back I copped a feel of the dough so that I would remember the texture the next time I made it.

Behind me erupted a delightful slurping sound. I looked over to see his arms extended across the table, his hands clenched as if cradling a small egg. “Can you pour me some more tea?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said, walking over and making a pouring movement into his fist.

“Ah,” he said as he slurped again. “This tea is so sweet. It must be the fresh tea you brought from Los Angeles.”

“…”

“…”

He waited for me to take a sip. I hesitated. He assured me it wasn’t too hot.

Dad's rice cooker technique: Dowse a chopstick into the dry grains until it touches the base of the pot. Pinch at the point the chopstick surfaces. Then lift the chopstick so the tip is level with the rice surface, and fill to the pinched point.

After he finished his “tea,” Ye Ye slapped his hand on the table with excitement. He motioned me to stay seated and went to take out a package of ground pork from the freezer and the Chinese chive buds from the fridge. The pork was defrosted at exactly one notch above LOW on the microwave dial for exactly eight minutes. I washed the chive buds and cut them into precise 3/8th-inch pieces while my grandfather rummaged through the cabinet and came up with a bottle of soy sauce. Grappling with the fancy new pour spout, he mumbled my grandmother’s name like a Hail Mary. Then he started pouring.

And he poured.

And poured.

“Whee!!!” he giggled, flooding my chives into little islands.

Hello Mr. High Blood Pressure? I envisioned my father’s face after taking a bite of these dumplings. His face would go red. Steam would whistle out his ears and then he’d pull out that thing – the sphygmomanometer – to measure his blood pressure.

“Fish sauce!” Ye Ye said, ducking back into the cabinet.

“Isn’t that a lot of soy sauce?”

My grandfather laughed again, squirting fish sauce out of the bottle with sharp jabs.

“Shouldn’t we dump some out?” I asked, tilting the bowl back and forth to accentuate the sloshing.

“No no,” he said, wrapping his arm around the bowl and giving me a big smile. He turned his back to me, cradling the bowl, and began stirring the filling, using chopsticks in a controlled manner so the great sea didn’t spill.

After a few minutes he stiffened and looked at the contents of the bowl over the tops of his glasses. His hair stood straight up and his mouth opened. Very carefully, he balanced some meat on his chopsticks. He looked at the bowl, he looked at me, and then he stuck the chopsticks in his mouth.

“That’s raw!” I screamed, lunging for the chopsticks. Bad news, Dad. Ye Ye’s got trichinosis.

My grandfather ran. Ran. This guy, the Shuffle Master of the Universe, took a lap around the stove island, paused for a breather at the table, then sprinted for the sink, hugging the bowl the whole time. He rolled his eyes for a second before he spit the pork out. With drool running down his chin he turned and laughed at me. His eyes teared up with joy. He laughed so hard I could see my own reflection in his fillings. I stood there, dumbfounded, watching his tongue waggle, him laughing so hard he had to rest both elbows on the counter, until it occurred to me that he had just tasted the meat to see if it was seasoned properly in the same manner he and my grandmother had done for over 50 years.

This method was something they had hid from my father, who probably had lunged and screamed at them the first time he saw them do it and scolded them never to do it again. My father, who could go off to work and come home to perfectly seasoned dumplings, had made it clear that bacteria was not welcome in his house. After our breathing returned to normal, Ye Ye and I looked at each other and laughed again, one last terrific laugh, each one eyeing the other for a sign of sanity.

Needless to say the dumplings were delicious, and my grandfather, as was his norm, ate two and a half platefuls of them. By my father’s quick calculation, using tableware specs and the size of an average dumpling, that makes for fifty dumplings, plus-minus one.

text and illustrations by Angie Lee

Angie Lee is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles. Her work has been published in Witness, Diagram, Airshipdaily and Entropy. She sells Chinese tea and teapots at 1001plateaus.com and offers tastings with Linda Louie from Bana Tea Company at Huntington Gardens in Pasadena. Angie blogs about tea, coffee and dogs at moonquake.org. Technically she eats Chinese food every day.