Authentic Beijing Tacos

A few summers ago, a pair of 22-year-old Chinese-Canadians, Wesley Lai and Kenneth Situ, applied to operate a food stand at the Richmond Night Market in British Columbia, Canada.

The Richmond Night Market offers a rare panoply of regional Chinese snacks and street foods. You can find roujiamo, Shaanxi-style gravied pork and peppers folded into a biscuit. Xinjiang Man BBQ serves yangrou chuanr lamb skewers. Wesley Lai estimates a little more than half the visitors to the summer night market are Chinese; in the Vancouver metro area, 30 percent of the population speaks some dialect of Chinese. The authenticity of the offerings at the night market played out to the detriment of Lai and Situ's venture.

The market doesn’t allow first-year vendors to hang their shingle with perennial market favorites like bubble tea or grilled squid skewers. “Bunch of people are already selling it,” says Lai. “So we decided nachos might be a good idea. But then we took that and kind of made our own creation.” The result was magic: Not Yo Nachos, featuring kimchos, a platter of corn chips sopping with kimchi and imitation crab meat; and japachos, topped with seaweed, onion relish and a squirt of wasabi.

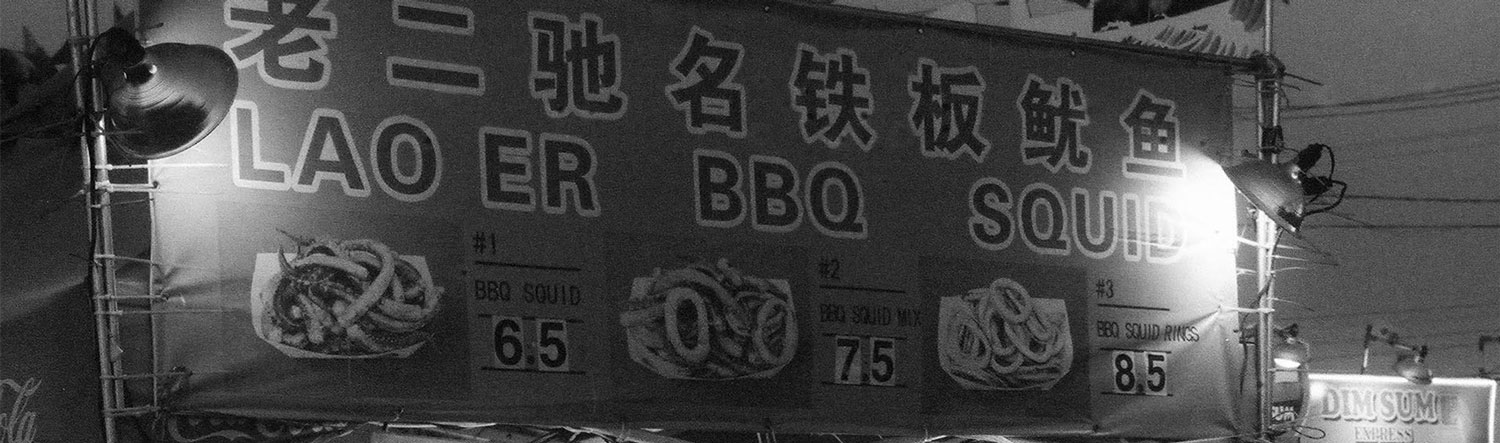

The bold products attracted media attention from outlets as far off as the Los Angeles Times, but failed to win over market regulars. Says Lai: “Nachos are not something they have in China, right? So to them it’s totally a new thing.” Rather than try something unexpected, market-goers fell back on the tried and true – namely, bubble tea and squid skewers.

By the end of the summer, Lai and Situ barely broke even, despite the international reputation they earned for themselves and their nachos. For the next year's night market, Lai and Situ retired Not Yo Nachos. “It’s a good product and all,” Lai says, “but profit-wise, not as great.” Instead they transitioned into frozen yogurt.

As the saying goes, 旧的不走新的不来.

If the old doesn’t go, the new won’t come.

When I moved back to the US after a five-year hitch in Beijing, the urban cauldrons of the North American Pacific coast had already begun to spill their streetwise concoctions – the ones that hadn’t gone the way of Not Yo Nachos – eastward across the continent. A food truck on the bar strip of my Midwestern hometown sold doubled-up corn tortillas, folded around teriyaki chicken, and dolloped with scallion-cilantro salsa. Wandering through Manhattan’s East Village, I stumbled onto a storefront advertising Vancouver japadogs – hot dogs slopped with condiments like yakisoba noodles or tonkatsu Worcestershire. The first bites from these West Coast exports tasted like new technologies, fresh and full of promise.

I got in mind one day to make Beijing tacos. The recipe was simple. Six-inch flour tortillas warmed on the grill. Marinated chicken thighs sheeted with a honey-hoisin glaze, roughly cut and forked apart. Napa cabbage sliced thin and tossed in a sesame vinaigrette. A fat bowl of Beijing-style sesame dipping sauce for drizzling.

Beijing tacos, like japadogs and kimchos, are a kind of a Zen koan to chew on. The more you try to situate them, the fuzzier they become. Wesley Lai instinctively classified Not Yo Nachos as Mexican food, even though his nachos were dressed with seaweed – even though nachos as we know them today, supporting a lava flow of melted cheese and pickled jalapenos, emerged from the bumping together of Mexicans and Anglos across the arid borderlands of the American Southwest. Not even tacos are eternally Mexican. Keep digging and eventually you’ll crack through to open air.

Except, having acknowledged the immateriality of the boundaries defining the Beijing tacos, I am sure they were real. I know because I took one in my hands and ate it.

More than one.

And they were good – good like the first time you fingerswiped on an iPhone.

Tortilla is not tortilla

“Fear not,” writes Gustavo Arellano in Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. “Mexican food is coming to wow you, to save you from a bland life, as it did for your parents and grandparents and great-grandparents. Again. Like last time – and the time before that.”

Arellano is the syndicated columnist behind “¡Ask a Mexican!,” a regular column in the OC Weekly that claims to respond to reader letters. (A 2013 column answered the question: “Are Mexicans violent because of their Aztec blood?”)

Although Arellano’s definition of the word “Mexican” never clarifies, his linear approach to the cuisine leads to some grating anachronisms:

“The world has loved the heat of Mexican food ever since its first encounter with it. It was the promise of peppery spice that drove Columbus across the Atlantic.”

In fact, as food historian Jeffrey M. Pilcher points out in Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, “Mexican food has been globalized from the beginning” – which is to say there is no rice and beans without Old World rice, no carne asada without cattle ranches, no queso Chihuahua without Mennonites immigrating to the Mexican state of Chihuahua to avoid compulsory enrollment in Canadian public schools. And that’s not even mentioning the borderland crosscurrents that defined the global experience of Mexican food in the latter half of the 20th century.

The history of the corn tortilla can be traced, with some space for wiggles, to the far side of the conquistadors. But flour tortillas are the bastards of cultural collision. No one knows who first ground wheat of distinguished European ancestry and flattened it into the shape of a humble Indian griddlecake. Origin stories attribute the first flour tortillas to Catholic priests in need of communion wafers, or Jewish refugees from the court of Ferdinand and Isabella, hungry for matzo.

The only tortillas I ate in China were at the KFC just outside the Line 2 Andingmen subway stop. One of the menu items, the Old Beijing Chicken Roll, took traditional flavors from Peking Duck rolls and did them up like a burrito – deep fried tenders, swabbed in a sweet plum sauce and rolled in a tortilla with cucumber slices and green onion spears. The tortilla stood in for chunbing, the steamed crepes traditionally served with roast duck.

KFC chicken rolls were a guilty pleasure, but one that tasted, somehow, like home. A burrito, whether stuffed with carnitas or bulgogi, ends up tasting like a burrito. There is something comforting about the shape of a meal, no matter the ingredients. A platter of nachos, regardless of what goes on top, hums a lullaby of baseball games and the neighborhood cinema. For all their thrills, cut-and-paste substitutions like kimchi for queso and imitation crab for ground beef amount to unexpected flavors in a familiar package.

Eating across China, I developed an unconscious habit of forming foods into the shapes from my upbringing. I tore open the fluffy dough of a steamed mantou and stuffed it with the peppers and pork belly from a plate of huiguo rou. I’d cap the mantou and swab it in oil and chaw down. My Chinese mother-in-law called this a mantou sanmingzhi – a mantou sandwich.

To me, it was just the way to eat food – to push and prod until it took a familiar shape.

Wings are not wings

It was 1981 when the Asian antiques dealer David Kidd, who, like me, lived in China for a formative period in his twenties, returned to Beijing for the first time in 30 years. His old expat friends warned him not to visit. “It is no longer the city of lingering splendor you remember,” they said. But he went anyway, motivated by that morbid curiosity that lashes us to our own histories. Kidd documented his recollections in the final chapter of his memoir. As he drove down the Second Ring Road, his memories of an otherworldly Peking – proud walls, looming gates, babbling alleys – confronted the brutal reality of the modern city.

“When I looked down at the oddly empty highway and the blocks of ugly new buildings, where the walls had stood, stretching north and south along the perimeter of what had been the most fabled walled city in the world, I experienced for the first time the anger that would save me from despair during the days to come.”

The destruction of civic landmarks still rankled native Beijingers during my time there. I heard regular harangues against the dismantling of Beijing’s city walls, which had taken place 45 years earlier. Cab drivers worked themselves into hoarse furies, pronouncing that act as one they could never forgive or understand. The fortifications had once ringed a feudal city of fine tilework and crooked alleys that bent and frayed into one another. Over the past 60 years, traditional hutong neighborhoods have been steadily demolished, ostensibly in the name of sanitation – many lack plumbing and relied on public toilets and bathhouses – or commercialized into Disney-like fantasies.

In the warren of preserved neighborhoods tumbling out from the Back Lakes (Houhai), there is a humdrum lane I know of that survived into the 21st century relatively untouched. Chaodou Hutong owes its lone historical significance to one Sengge Rinchen, a Qing Dynasty bannerman who built a mansion here 150 years ago before dying gloriously in battle against a rebel army. The hutong is obscure enough that most Beijingers wouldn’t recognize its odd name: 炒豆, meaning “stir-fried bean.”

Back in 2007, a cab would drop you off at the western mouth of the alley, which was too narrow for street traffic. You’d have to wander in on foot. The only reason to go was a chicken wing joint, unmarked except for a little drawing of a spaceman outside the door. The owners, a gang of local twentysomethings, named themselves the Hot Bean Cooperative. They were an eclectic bunch. One practiced traditional wrestling. Another was an amateur magician who never left home without an American half dollar in his pocket for sleight-of-hand tricks.

They skewered the wings in pairs to grill over a trough. The handwritten menu rated wings on a ladder of spiciness that began with “original flavor,” and passed through “single-side hot” – wings dipped on one side into dried chilli flakes – on the way to “double-side hot,” which was enough to drench your hat. The scale rocketed off with “perversely hot,” a fearsome hedgehog of chilli matted so thick the wings nearly doubled in size. This was more a rite of passage than a menu item.

Hot Bean wasn’t a see-and-be-seen destination. The walls were unfinished cement and there was no heating or A/C. Nevertheless, no one got a table without a reservation, not even in winter when you had to eat in your jacket and scarf.

Wings were the hip new trend in Beijing. If the American instinct for wings is to dredge them, fry them and toss them in buttery hot sauce, Beijing wings took a shape more familiar to the local palate: jabbed on sharpened sticks and thrown on the grill. You can get almost anything grilled on a stick in China. A streetside grillman once served me three chicken heads threaded on a skewer through the eye holes. (You ate the wattle and the comb, then cracked open the skull to get at the brains.)

Hot Bean offered up dishes that were uncommon to Chinese restaurants – personal grilled pizzas made from scratch, salad greens tossed in sweet vinaigrette and sprinkled with peanuts. But the draw was the wings, carried to your fold-out table in a metal pail with the skewers point-side down. Hot Bean wings were famous for the dry prickling crust that tore away and, like an opening oven door, filled your mouth with the warmth from the moist flesh inside. The menu gradually expanded to include a garlicky Korean-style wing, and another goopy sweet-and-sour offering they called a ketchup wing.

Some of my fondest memories of Beijing are the days I spent drinking beers on the Hot Bean terrace before the dinner hour, watching stray cats navigate the sea of tiled rooftops that peaked off toward the lakes. On winter afternoons, I’d find the gang in the courtyard skewering the evening’s fare. They squatted around a two-handled tub that bobbed with wings steeped in a pungent spell of fluids and bits – soy sauce, peppercorns, ginger slices, shimmering bubblets of oil.

In the US, when I got the hunger for Hot Bean wings, I tried to recreate that marinade by throwing together every seasoning I’d ever seen my wife cook with. All the liquids – dark and light soy sauce, dumpling vinegar, rice wine, chilli oil, toasted sesame oil; and then all the solids – ginger, garlic, green onions, cilantro, sesame seeds, dried chilli. I won’t say I ever pulled off authentic Hot Bean flavor, but I did make some passable wings.

Over time I came to employ that same slapdash marinade on all my grilled chicken. I took a liking to thighs. All that skin and dark meat makes for a fine texture, plus Costco sells thighs in vacuum-sealed packs of 32. I carve the bones out to save for stock and carpet a hot grill with meat for sandwiches, or wraps, or sprinkling over a summer salad – or mincing into chunks for tacos.

Dipping sauce is not dipping sauce

Xiao Ma, the wrestler from the Hot Bean Collective, used to invite me and the gang for hot pot at the south-side hutong where he lived with his parents. Ma’s neighborhood had been under threat of redevelopment for years. A few alleys down, the wrecking had already begun. If you followed a turnoff through his alley, you’d suddenly emerge in a half-leveled field of rubble.

I must have heard a hundred explanations across China about the origin of hot pot. Depending who you ask, the credit may run to Chongqing rivermen or Mongolian horse archers. The most satisfying legend begins with Kublai Khan readying a field banquet of stewed lamb when an aide dashes into the tent. The enemy has launched an unexpected attack! Angry and hungry, the Great Khan slices his lamb very thin so it will cook after a quick dipping into a simmering broth. He gobbles the meat down and rides off to victory. Hence the name for northern-style hotpot: Dipped Lamb Meat.

Xiao Ma’s father was a king of Dipped Lamb Meat. His secret was the majiang, the dipping sauce for the cooked ingredients. One of my last nights in Beijing, I visited him to learn his recipe. Although the house was closet-sized, it was also a single-story residence – a point of pride in a city dominated by residential towers.

“You want to make majiang when you go back to your country?” Old Ma asked me. “I’ll tell you how. Start with some sesame paste. The restaurants want to earn money, so they’ll dilute it with water. But the Beijing way?” He snatched up a bottle. “Sesame oil!” He stirred it into the paste with his chopsticks, clockwise. “Use the oil to open up the paste. Once it’s open, get the fermented doufu. Let me warn you, OK? Use fermented doufu – not stinky doufu.”

It plopped out of the jar in a squared lump.

“And break it into pieces.” He stirred again, this time counterclockwise. The paste thickened to the color and consistency of cream of wheat. “Then add the pickled leek flower. If it’s not salty enough, add some more. And also there’s one more thing I’ll tell you.” He disappeared out into the alley and returned with two bottles. The leek flower pickle had sharpened the air in the room. Old Ma allowed two drops of a dark rice vinegar and a brief tipping of soy sauce. “Not too much,” said Old Ma, “only for the flavor. Some people like to put in MSG or bouillon flakes. Use them if you like. But here we like the old taste, the original flavor.” Now the majiang slopped up around the brim of the bowl when he stirred. “And we’ve made it.”

The taste was full and strong-boned, not sweet and not salty. It was worth five years of my twenties, I think, to bring this sauce back from China. It is one of the proudest flavorings in the world, and tinkering with the proportions results in nutty dressings and drizzles and undertones of a world that has yet to appear in the American culinary lexicon.

Change is not a change

Human beings, all the way back to Adam, are categorizers. Finding patterns in the vast realms of data collected by our senses eases the working burden of the mind. But hybrids scramble our categories. A Chinese taco is neither one thing nor another. The Nobel Prize-winning poet Octavio Paz famously condemned fusion foods as ostentatious and fake.

“Eclecticism has inspired many cooks to invent hybrid dishes and other palate-pleasers. The ‘melting pot’ is a social ideal that, when applied to culinary art, produces abominations.”

The English language has its fill of words that express Paz' revulsion – bastardization, perversion, miscegenation, hybridization, the mulatto and the half-breed. These perversions come about, perhaps, by circumstance. When my mother-in-law visited Chicago, she couldn’t find a particular pepper, so she cobbled together a batch of pork and jalapeño dumplings. After a trip to the Vietnamese markets on Argyle Street, my wife folded up a batch of beef dumplings seasoned with fish sauce and Thai chillis. Such wondrous miscegenation!

I don’t know if they were Mexican or Thai or Chinese dumplings. I don’t know whether flour tortillas are Mexican by way of Jewish exiles or Jesuit priests, or if hot pot is Mongolian or Manchu or Sichuanese, or if the japachos are Tex-Mex or Japanese or Canadian. Enough to call it food, recast from our histories into souvenirs for the ones who come after – an inheritance from the stirrings of peoples and the toppling of barriers between them, a memory of things we eat to recall the places we’ve been and the people we were.

MAKING AUTHENTIC BEIJING TACOS

Bone the thighs and marinate them in whatever you’ve got on the shelf. Definitely use soy sauce, some kind of dark vinegar, garlic, ginger, toasted sesame oil and something spicy. Let them sit for a while and then grill them.

Mix hoisin sauce with something sweet from your cupboard. Maple syrup, molasses, honey, even a berry jam works. Spot this with garlic, ginger, and sesame seeds. Glaze the thighs with this on the last turn of the grill.

While the thighs are cooling, make the majiang according to Old Ma’s instructions. You can find all the ingredients at a good Chinese grocery: sesame paste 芝麻酱, sesame oil 麻 油, fermented doufu 腐乳, leek flower pickle 韭花酱. This is your salsa.

Toss thinly sliced cabbage with a vinaigrette of sesame paste, vinegar and toasted sesame oil. This is your crunch. Mix together some sliced green onions with roughly minced cilantro for a garnish. Chop the thighs into strips or chunks after they’ve had a few minutes to recover from the grill. Fold a pinch or a spoon of everything into warm flour tortillas and eat barehanded.

photos by Matt P. Jager and Dave Vondle

Matt P. Jager believes Chinese food can save lost souls. His research interests include Manchu campfire cooking and the foreign experience of food in wartime China.